Return to Monke (Learn to use git branches)

Return to Monke

how you should stop merging everything and learn to rebase from time to time

Recently I’ve seen how people are scared of using git branches and how rebase seems like this incomprehensible tool to destroy your history and reenact the Minitrue from 1984.

I used to be like you: “Branches are for monkeys”, I would say, but then I understood that even when you think you are always working on the trunk, on your main and only branch, you are still using more than once branch, and you should return to monke and learn to swing on those branches.

This is a part of my “git gud or git rekt” series

WTF Is a branch anyway

Git is a marvelous tool, but it’s not as scary as you might think, for the scope of this article, we can consider that a branch is just a pointer to the last commit of that branch.

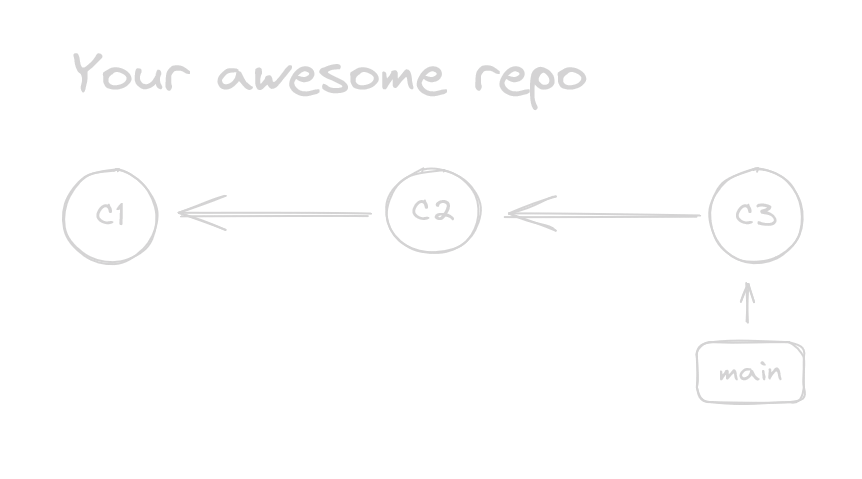

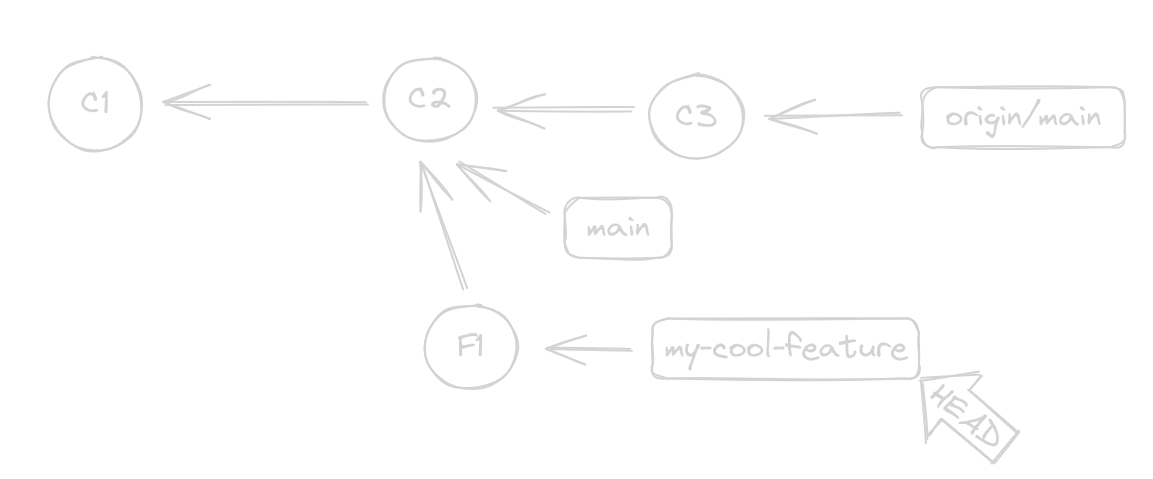

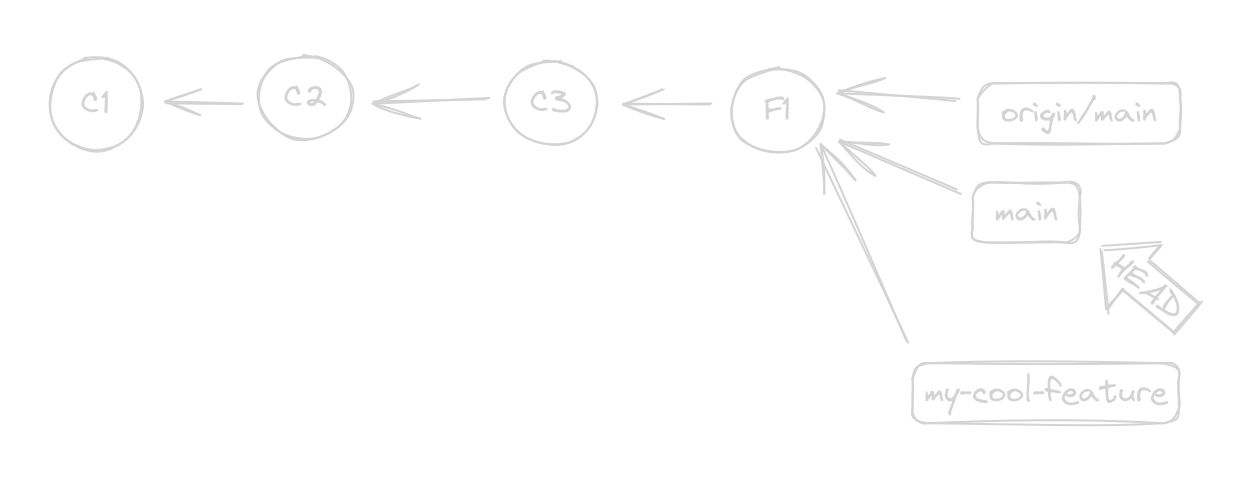

And if we remember that a commit is just a pointer to their previous or parent commit, this graph should make sense to you

Just in case: remember that commits point to the previous commit in history. In this graph the past is at the left and the future is at the right.

You use branches every day and you don’t realize

You might think that you don’t, after all you are a trunk merging connoisseur, obviously you would know if your delicate hands touched a branch… right?

There is the “uploaded thing”, you probably call it “GitHub” or “the pushed repo” but git calls this remote and the default one is usually called origin.

To handle the fact that this remote has different changes to what you have locally, git tracks the remote upstream branch as origin/main (name of remote/name of branch)

Your local repo isn’t always in sync with “the uploaded thing”, sometimes you pull, sometimes you push.

Well, have you ever git pull before? What if I tell you that what you did was use a shorthand for two commands: git fetch and… git merge! dun dun duuuuun

Let’s break it down:

git fetchmeans “go to the online thing and download the branch to my pc.”git mergemeans “now, grab that branch you download it and slam it against my local branch until something happens.”

But wait… so you actually download the remote branch before merging it with the local things? MADNESS!

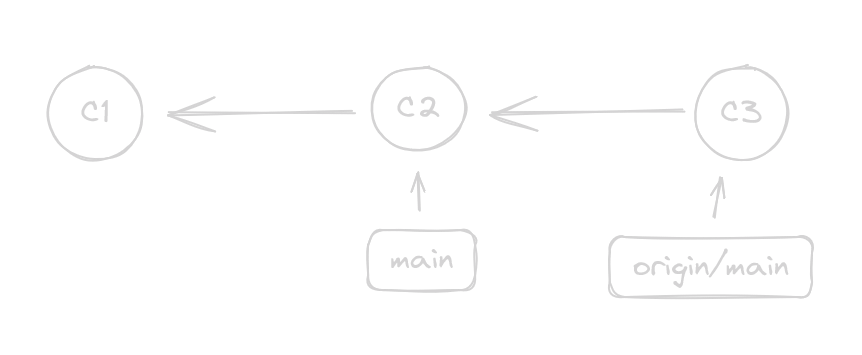

Yes, you do. Now, look at this graph:

Here you might say “There are no branches, it’s just a straight line with no bifurcations”.

Here you might say “There are no branches, it’s just a straight line with no bifurcations”.

If you do, please read the previous section, where I told you: “a branch is just a pointer to the last commit of that branch”.

This is the same graph as before, it just looks different, but the arrows point to the same place so it’s the same.

This is the same graph as before, it just looks different, but the arrows point to the same place so it’s the same.

This graph has two boxes: main and origin/main. There are two branches.

Git will call this something along the lines of “You are 1 commit behind”.

Your first branch swing

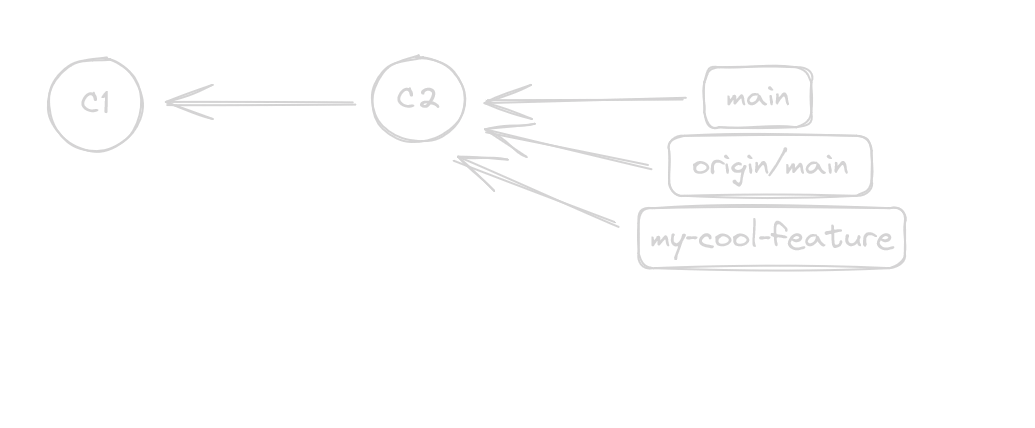

Let’s take baby steps, let’s say you just cloned a new repo, you have main up to date, and you now need to branch out to make a new feature because some eeeeevil CTO forces you to use branches.

git checkout -b my-cool-feature

Again, let’s break it down

git checkout: It’s the git command to go places: branches, back in time, to alternate universes, etc. Read more about time travel in git-b: You won’t find the branch I’m about to tell you. Create it pls.my-cool-feature: The name of the branch you want to create. Your evil CTO should have some rules on how to name these.

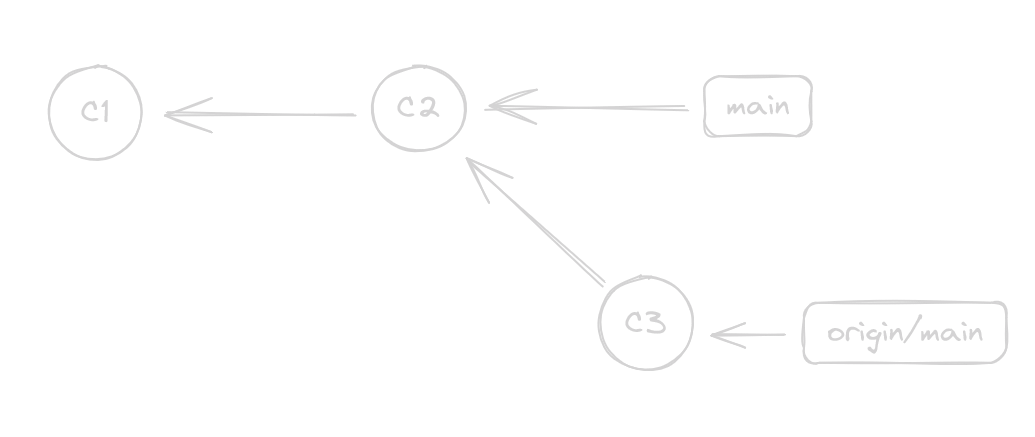

The graph now looks like this, pretty uninteresting

If you push your new branch, you would create a new branch called

If you push your new branch, you would create a new branch called origin/my-cool-feature that would also point to the same commit

Now, let’s make some commits in our feature (we will mark them with F) and some commits in main so we diverge

if you are confused by the HEAD thingy, you should check the How to Time Travel in Git but for now, consider it the “you are here” of git

Now, we see that not only we have diverged with our my-cool-feature from origin/main but main is outdated!

The easy step first, with git checkout main (we no longer need the -b because main already exists) we move HEAD to main and we can git pull and we have main up to date.

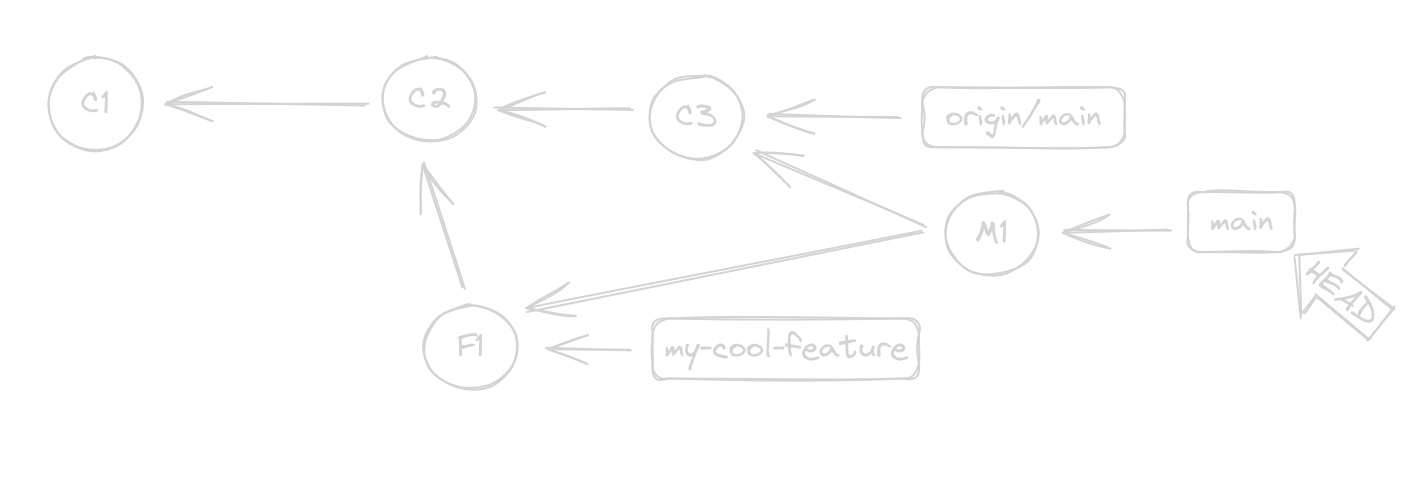

Now, since we are still not illuminated monkeys, we can just git merge my-cool-feature.

Let’s break it down:

- We are in

main git merge: “grab a branch and slam it against the branch I am in until something happens”my-cool-feature: The name of the branch you will slam against the one you are in

This will look like this, and M is a Merge Commit

At this point, you are “1 commit ahead” and can git push to send your changes.

| But look at that commit… That Merge Commit… What makes it a Merge? The name? The contents? You probably didn’t even make it, it… just kinda happened : |

A Merge Commit is a commit with TWO previous commits

You see now that it has two arrows pointing back? Your commit is now a quantum collapsed multiverse child. An absolute point in time in which two timelines crashed together, and somehow a single line continues forward.

(In this case, we only merged two timelines, but there is something called an “octopus merge” that can merge many timelines in a single commit.)

To sum up, to fix the timeline we had to create one of these “Merge” commits thingies… but we had no choice… right?

Rebase without rewriting the past

Usually, when people think of rebase they think of destroying the history, rewriting it 1984 style and then git push --force to erase all proof that stuff ever existed…

And while you can use rebase for that… you can also format your hard drive, cut your internet wire, put a fork in a toaster… but you don’t have to. (please, don’t put forks in the toaster)

What does rebase do?

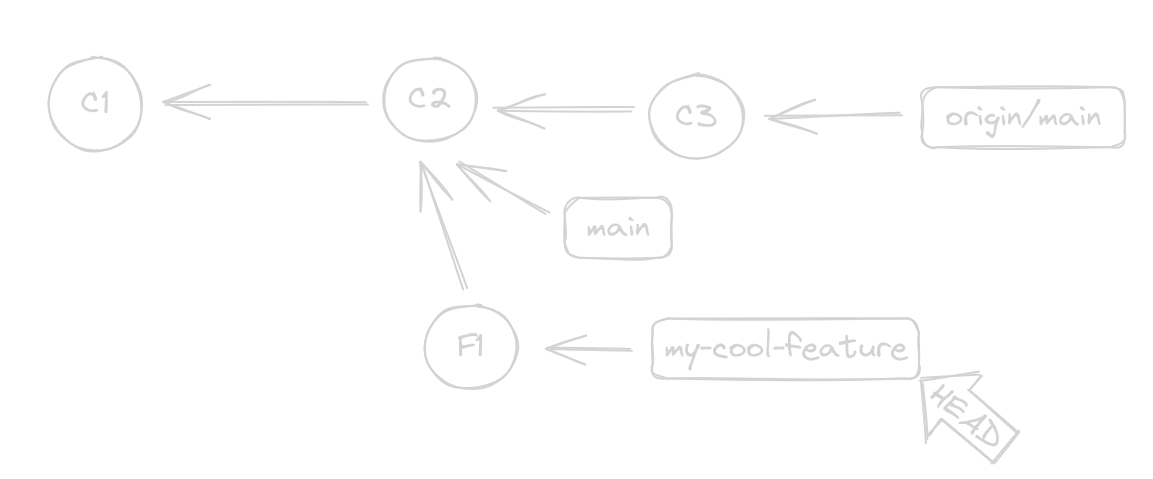

It basically means “Change from where in time this branch split off” Let’s go back to this example:

HEAD is in my-cool-feature and we can see that we branched the timeline at C2.

C3 happened sometime after we did our F1, but since the origin/main timeline doesn’t know our F1 happened, it really doesn’t care if it happened after C2 or C3… so what if we could do this

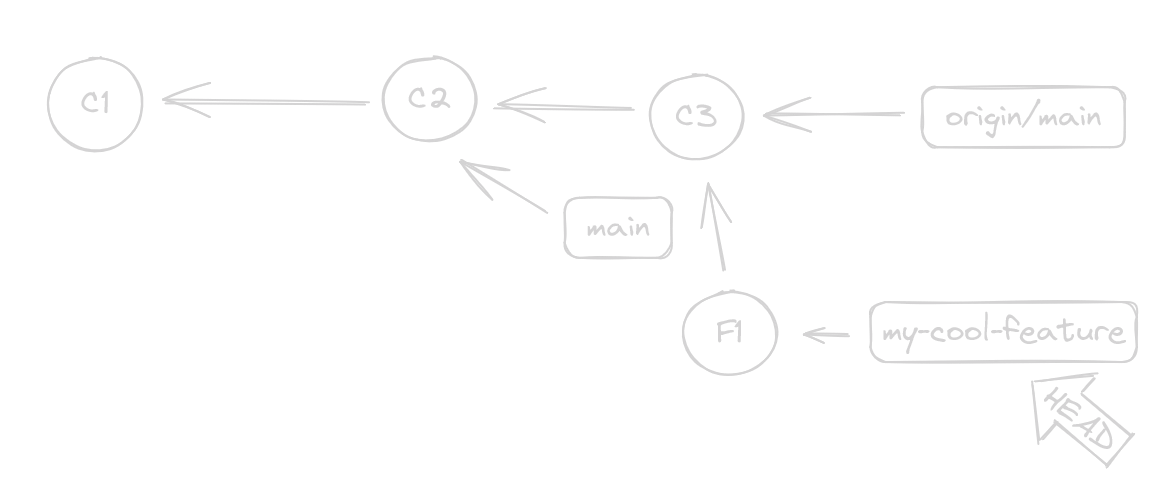

git rebase origin/main

(Remember, our head is on

(Remember, our head is on my-cool-feature)

Let’s break it down:

HEADis onmy-cool-featuregit rebase: Let’s change where we split off from the timeline.origin/master: This is the point where I want to split off from the timeline.

Now, hopefully you can see it, but we are actually “1 commit ahead” of origin/main. This means we can merge without a pesky Merge Commit

By now, I hope you can follow these commands:

git checkout main: Move tomain… butmainis outdatedgit pull: Syncmaintoorigin/maingit merge my-cool-feature: But… wouldn’t this create the dreaded Merge Commit?

In this case, Git is smart enough to know that the time split happens from now on and into the future, and performs a Fast Forward Merge that ends up looking like this

Isn’t this pretty? We didn’t lose any commits, we didn’t rewrite any history, we did not create a totalitarian state, and we have a flat timeline without these quantum anomalies that have many pasts.

So is rebase “just better”?

Nope. They are just different.

You probably have used merge all your life and didn’t even know it, and probably can continue to do so.

The downsides of merge are that they muddy the water on who modified what and where given that these Merge Commits have two parents.

The biggest downside from merge is when working with binary files and LFS locks. If you use LFS Locks you MUST use REBASE.

AAAAAAA I did something wrong, and I am stuck in a rebase and I don’t know how to fix it, and I am scared!!!11!1one

git rebase --abort

This will stop the rebase and undo everything to exactly like it was when you ran git rebase

But rebase can rewrite history, right?

Yes, it can. The topics are “squashing” and “interactive rebase”. I won’t cover those here.

Unless you know exactly what you are doing or your evil CTO asked you to do them, I advice to not squash.

Thanks for reaching this far into the article!

All my drawings are excallidraw embeded so you can download the png and edit it directly or if you want the full editable file you can find it here

See you in the next one!