Unity WebGL compression done right

Unity WebGL compression done right

If you ever exported and tried to publish a WebGL game made with Unity, you were probably bombarded with really odd dichotomies like “you can either have a good compression rate (brotli), but you need to do this wacky server setup and run the game in https.” or “You can let us run the decompression, but your game will be heavier than if you didn’t apply compression to it.”

Why? Well, because Unity tries to reinvent how the web works, and in true Unity fashion, nobody asks why we are using a tool that was not designed for this (I am looking at you yield return for async stuff, but that is a different rant).

Overview of the Unity settings and what they mean

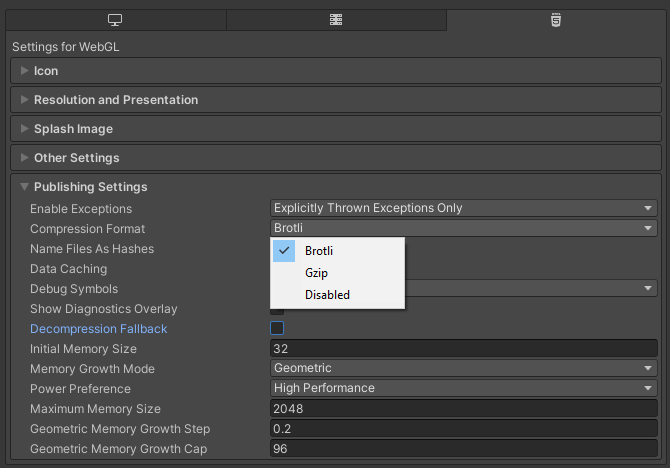

Ok, I am using Unity 2022.3.30.f1, but I’ve seen these settings since the dawn of the yearly versions, and I can bet that they won’t change anytime soon.

The settings we are going to focus on are:

- Compression Format

- Brotli: Unity will only generate

.wasm.brcompressed files and download them directly, hoping for the browser to know how to decompress them. - Gzip: Unity will only generate

.wasm.gzcompressed files and download them directly, hoping for the browser to know how to decompress them. - Disabled: Unity will only generate

.wasmuncompressed files and download them directly (no decompressing is needed)

- Brotli: Unity will only generate

- Decompression Fallback: Unity will generate the format you specified above but will append the extension

.unityweband decompress your files in javascript manually (as opposed to letting the browser decompress them).

Unity makes some observations about how the different formats work; let me paraphrase them with my own words:

- Brotli: Slow as hell to make a build, but results in the smallest possible file size. Your browser must be Chrome or Firefox (wrong, Safari has supported it since 2017), the game must be served over https, and the server must be specially configured, or your game won’t work.

- Gzip: Faster to build, slightly worse compression than Brotli. It works on every browser; the game can be served over https or http, but the server still needs to be specially configured, or your game won’t work.

- Disabled: Fastest to build, no compression at all. Works everywhere, no special configuration is needed.

- Decompression Fallback: Unity embeds a decompressor made in javascript and instead of letting the faster broswer decompressor run, it uses the javascript one. This is slower, but it can help you if you can’t or don’t know how to configure the server specially for Unity.

If you paid any attention to my bolding, you should be starting to pick up my issues with how Unity works…

- “The game won’t work” is unacceptable.

- Why limit yourself to only one format and not have all the formats available?

- Why do we need Unity special settings on our servers? Are we special internet snowflakes, or are we just reinventing standards?

- Decompression fallback is silly and can bring other problems like double compression (servers compressing an already compressed file).

If I managed to get you hooked, please keep reading to learn how the internet actually works and how we can tweak Unity to play nice with it.

How the internet actually works

We make games, and not only that, but we make web games. Our players have the attention span of an ADHD-ridden goldfish, and if we don’t manage to load our game fast, we lose them. That’s why we want the smallest possible download and the fastest meaningful print possible.

However, the rest of the internet has their own reasons to send the smaller possible file, and that is the fact that sending a large file uses more compute time on the server and more bandwidth, and those are things servers pay for, so the smart people that make the internet work already designed a way to send compressed files.

I am going to explain this as a conversation, since this is pretty much how the tcp/ip protocol works.

- Browser 1

- Hello, good server, I need the file called “index.html”. By the way, I know how to decompress

brandgzipformats.

- Hello, good server, I need the file called “index.html”. By the way, I know how to decompress

- Server

- Hello, my good browser, I have the file right here, and wouldn’t you believe it, I know how to compress it in

brandgzipformat too! I am sending thatindex.htmlfile you requested, but I compressed it asbrso please, before using it, decompress it.

- Hello, my good browser, I have the file right here, and wouldn’t you believe it, I know how to compress it in

- Browser 1

- (takes the file and decompresses it before giving it to the user)

- Thank you very much.

And, scene! What a nice interaction, with the browser telling the server exactly what they wanted and the server doing the right thing! The important thing here is that the server has the original file, so look at the following case:

- Browser 2

- Hello, good server, I need the file called “index.html”

- Server

- Hello, my good browser, I have the file right here. I am sending that

index.htmlfile, and since you didn’t tell me that you know how to decompress file, I didn’t do any compression to it.

- Hello, my good browser, I have the file right here. I am sending that

- Browser 2

- (takes the file)

- Thank you very much.

Another beautiful scene where the browser and the server communicate and work together. This time, the browser didn’t know how to decompress files, so the server knew to send the original file.

But enough with the analogies; what does this all mean? Well, when a browser makes a request, one of the headers that the browser sends to the server is Accept-Encoding which indicates the compression formats that this browser can handle.

Accept-Encoding: br, gzip

In return, if the server supports one of the formats, it will either compress the file on the fly before sending it or grab a pre-compressed one and send it with the header Content-Encoding to indicate which of the formats that the client suggested was used.

Content-Encoding: br

If the browser and the server do not share a valid compression format (or the server, for any reason, doesn’t want to send a compressed file), the original file requested is sent. No harm, no foul.

How Unity attempts to make it work

If you look at my examples before, the browser always asks for the actual file they want (and provides options for compression formats) and never for a specific compressed version. e.g., index.html and not index.html.br

Our javascript code directly asking for a compressed file will end up getting us a compressed file, and since the browser did not ask for the compressed version and the server didn’t know it was sending a compressed version, the browser won’t decompress it, and it will be up to javascript to decompress the file!

Unity tells you that this is obviously the server’s fault. It should have been obvious that if you asked for a br file in your javascript code, you didn’t really want that br file, but you wanted the browser to decompress the file and give you an uncompressed file with a .br extension, and for that, the server has to go against what the browser told them to do and say that the br file was compressed.

You do this gaslighting job by hardcoding into your server that all files ending with br served must be served with Content-Encoding: br even if the browser requesting the file doesn’t know how to handle it.

But first, let’s try with an unconfigured server. Without the hardcoded Content-Encoding that Unity says you should do.

- Browser 3

- (Unity javascript code has asked Browser 3 to download

Build.wasm.br) - Hello, good server, I need the file called

Build.wasm.br. I can only understand thegzipcompression format.

- (Unity javascript code has asked Browser 3 to download

- Server

- Hello, my good browser. I have the file right here. I am sending that

Build.wasm.brand even if we both speakgzip, to keep this example simple, I will not compress it asgzip. I am sending the original, unmodified file you asked for.

- Hello, my good browser. I have the file right here. I am sending that

- Browser 3

- (Takes the file and gives it to the unity javascript code)

- Thank you very much. I didn’t do anything to the file, as we agreed.

- (Unity receives a still compressed Brotli file and crashes)

Damn, surely it was your server fault that Uunity asked for a file that it couldn’t handle, right? Let’s make sure our server knows that all br files must be served with Content-Encoding: br

- Browser 4

- (Unity javascript code has asked Browser 4 to download

Build.wasm.br) - Hello, good server, I need the file called

Build.wasm.br. I can only understand thegzipcompression format.

- (Unity javascript code has asked Browser 4 to download

- Server

- Hello, my good browser. I have the file right here. I am sending that

Build.wasm.brand even if you don’t understandbr, Unity told me to hardcode and tell you that this file is compressed asbr.

- Hello, my good browser. I have the file right here. I am sending that

- Browser 4

- Wait… what? Nononono I can’t decompre…

- (Browser fails to decompress br as expected. The user gets a cryptic “network layer error”)

You just killed a perfectly healthy browser. Are you happy?

The server had all the information to know that this would kill the browser, but Unity not only ordered him to kill the browser but also the build process didn’t generate any uncompressed files!

Even if the server wanted to save the day, we didn’t give it a file that would work for that browser!

You could now argue that since every browser should support br by now, this wouldn’t happen, but since br only works over https connections, it could still happen. Even with gzip, this could still happen.

How we can actually make it work like the internet wants

Since normal web traffic is small, web servers are configured to compress the files on-the-fly as they are sending them. However, our files are sliiiighlty larger than what the web expects… close to 20000 times larger (20mb vs. 1kb), rendering on-the-fly compression unviable, so we can provide pre-compressed files and tell our server to serve those to the clients if they support it (this is the default behaviour for some servers and in some others is just one line of config).

But first, we need our original files and then compress them.

Getting original files is easy; just set the Compression Format to Disabled (and obviously Decompression Fallback to false). That will give us uncompressed files but, now we need to compress them.

There are official implementations for both brotli and gzip but I am going to use a javascript based tool just for ease of use: gzipper

(This being a javascript based tool, you need node and npm to run it, but since we are doing web development, I assume you have them)

Get the tool with npm i -g gzipper (or, if you are a cool kid and know how to use npx, use that)

And with that, we can gzipper compress Build.wasm --gzip --brotli --zstd (zstd is another format that we can throw it in for good measure).

But why stop there? Why not try to compress all the “big” files that our build has? Well, we can do exactly that with this command:

gzipper compress ./Build/ --gzip --brotli --zstd --gzip-level 9 --brotli-quality 11 --zstd-level 5 --threshold 256000 --remove-larger

so…

gzipper compressto compress files../Build/the path to your entire build folder.--gzip --brotli --zstdthe three formats we are creating.--gzip-level 9 --brotli-quality 11 --zstd-level 5setting the max compression settings for our 3 formats.--threshold 256000don’t compress files smaller than 256kb. Files this small are easier for the server to compress on the fly.--remove-largerif, for some odd reason, our compressed file ends up being heavier than the original, delete the compressed version.

This will create compressed copies of all our heavy files, and a server could use those instead of the original ones.

To try, I will boot an http-server with the following script :

(Remember: npm i -g http-server and you will probably need some sort of openssl installed. If you have git you should have it).

cd Build

openssl req -batch -newkey rsa:2048 -new -nodes -x509 -days 3650 -keyout key.pem -out cert.pem

http-server -c-1 -S -g -b

cd Buildnavigates to the build folder.openssl req -batch -newkey rsa:2048 -new -nodes -x509 -days 3650 -keyout key.pem -out cert.pemcreates a fake https certificate.http-server -c-1 -S -g -bopens a server with cache disabled and https and compression enabled.

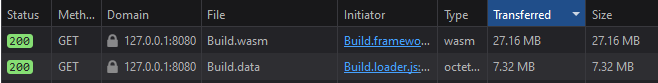

First, let’s see how the build looks in the network tab before compression:

Here we can see the “Transferred” and the “Size” of our uncompressed files. “Size” refers to the original file size (before compression), and “Transferred” is the actual amount of bytes sent through the network.

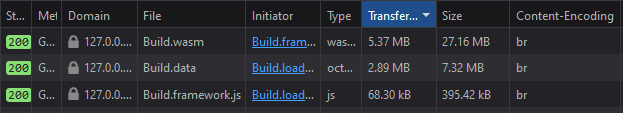

Now, let’s compress our files and try again:

Here you can see that we downloaded only 5.37MB which decompressed to 27.16 original megabytes. That’s AWESOME!

I added the Content-Encoding column so you can see that what we are using is the br encoding.

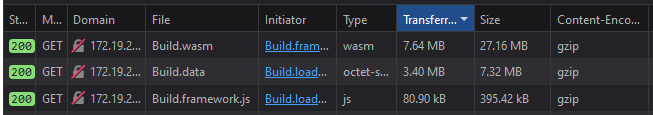

We were able to use br as we are running an HTTPS server, but let’s see if we use HTTP

Since br is not supported under HTTP, it falls back graciously to gzip, and you still download less than the original size, and your game loads as fast as possible!

And since we requested a .wasm file and no hacky wasm.br file, the server that sent the file and the browser that received the file understood that it was a wasm file all along, and thus, the Content-Type header is correct, and the call to WebAssembly.instantiateStreaming managed to compile and run our code while it was downloading making it load even faster!

If you make it this far, congratulations! You now know how compression works in the web world!